Since October 2012, Ralf Grötker from Debattenprofis has been conducting a media experiment involving argument maps and swarm intelligence. In the so-called Faktencheck (Factcheck) series, Grötker sets up and moderates online forums on controversial issues (e.g., “boycott of textiles — helpful or not?”). Debattenprofis use argument maps to aggregate the discussions. In a recent article Grötker sums up his experience so far.

This is how Grötker describes the overall design of the experiment:

“Faktencheck” brings together elements of reader participation and journalistic investigation on controversial issues with a scientific background. There’s a live investigation for a period of 3 days. Readers have the opportunity to join the investigation in a forum. A moderator transfers both comments in the online forum as well as other results from the investigation into a so-called argument map.

According to Grötker, the role of argument maps was ambivalent. On the negative side he notes:

The great hope, which we associated with using argument maps, was that it would be feasible to somehow order the discussion in the forum. In this regard, the experiment was rather disappointing. Only a few commentators made use of the opportunity to refer directly to the branches of the map. At closer look, however, this is hardly surprising: In many contributions, commentators looked for engaging in a dialog — mostly, by the way, in an astonishingly respectful way.

Let me jump in here. It’s clear from a brief look at the webpages which document the experiment that the argument maps didn’t help to structure the online discussions. So, is argument mapping in general unsuitable for such a task? I’m not prepared to draw this conclusion yet. As has been noted by participants of Faktencheck before, it seems a major problem that the argument map is totally disconnected from the online debate.

- The arguments in the map don’t link to the contributions they reconstruct. (Although some arguments contain roll-over quotes from the online discussion.)

- The contributions in the online forum, in turn, don’t link to arguments that represent the contribution, either.

- The argument map is, moreover, embedded on a different page than the online forum.

(To make things worse, the discussion seems to be conducted in several, separate online forums.)

That might explain why the map played virtually no role in structuring the discussion.

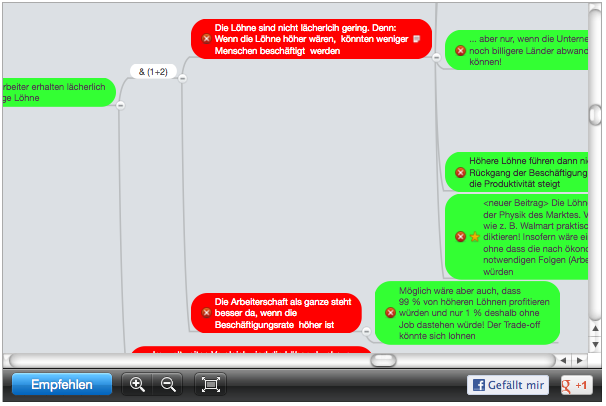

Another issue is the software Debattenprofis have used. Look at the startscreen of the map about textile boycotts:

That doesn’t look very inviting. Even more importantly,

- it’s really cumbersome to navigate the map, and difficult to get an overview;

- more specifically, it’s not straightforward to focus on one argument and its adjacent reasons only;

- the debate doesn’t exhibit a macrostructure;

- the hierarchical layout is very space consuming, which is a major disadvantage if the map is embedded.

Let me also note that the Faktencheck argument maps are not based on detailed reconstructions of the arguments advanced in the online forum, but merely “sketch” (as we use to say) the debate. As a consequence, the dialectic relations between the arguments are still provisional and seem to some extent arbitrary.

Ok, back to Grötker’s upshot, which also highlights a positive effect of argument mapping in the Faktencheck experiment:

The visualization fulfills an important function nonetheless. As the argument map strived to represent all pros and cons (concerning the corresponding claim), it goes along with a certain promise of neutrality. The opponents don’t have to agree on a common evaluation of the arguments in the map. But they have to agree that the controversial issues are comprehensively represented. This promise of neutrality was particularly helpful when we asked external experts to join the factcheck. The opinions of experts could enter the map without us being required to come to the same conclusion as the experts in our final summary — a fair set-up for all parties.

It’s an obvious virtue of argument mapping that it allows opponents at least to agree on what the arguments are and how they relate to each other. Also, to agree on an argument map doesn’t compel one to endorse a certain position. Faktencheck seems to have vindicated these argument mapping advantages.

To connect the dots, however, imagine an argument map browser that allows users to enter their assessment of the arguments (‘refute’ vs. ‘accept’) as they skim through the debate. This might not only enhance user experience but help to integrate the debate visualization and the online discussion.

Be that as it may, Ralf Grötker has conducted an exciting experiment and I’m looking forward to Debattenprofis’ future argument mapping projects!

Thanks for that interesting discussion. For what its worth, over about a decade I’ve gone from being an enthusiast about the potential of argument mapping to aid public deliberation, to a skeptic. My views are summarised in the article Cultivating Deliberation for Democracy. Ralf’s comment “this is hardly surprising: In many contributions, commentators looked for engaging in a dialog” is consistent with this view.

Thanks a lot Tim! It’s remarkable that you’ve eventually come to a sceptical conclusion. The criticism you advance in your “Cultivating Deliberation for Democracy” dovetails with some of my own experience: It’s certainly true that you must not expect internet users to articulate their reasons as premiss-conclusion-structures, for example. If you impose too much structure, you risk to suffocate the debate. This insight, however, leaves plenty of room for argument analysis in improving public discourse, be it as a (possibly behind-the-scenes) tool for moderators of discussion, or as a method to inform a (free-floating) controversy. I share our experience with our latest public policy project here. Your nice yourview.org.au or adhocracy.de are nonetheless a real improvement for online deliberation.

Thanks for your review, Gregor. Let me add a few things.

1. “Imagine an argument map browser…”: Sure: it would be great to have that. Also, I am eager to see the the argunet browser. That said, my own preference would be to test singel features in a rapid prototyping mode, rather than investing years into the development of a software which, in the end, might turn out not to meet the demands of users. (We all know examples of that kind of software in our field.)

2. A good benchmark for what one could wish to accomplish with arguments maps would be the use of much simpler instruments such as allowing comments in the side area of the text. There are a few wordpress-plugins for that (“paragraph comments” – like here: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-real-abortion-tragedy-by-peter-singer). But: no website of a major news website has this feature! I believe though, that we need these websites in order to get an audience. (Any other great software which not run on these wil thus be of limited use.)

The embedded mindmap we used is a workaround to deal with the situation just described. My obrservation: Embedding draws much more readers into the game than just re-directing them to a second site.

3. I would test for “argumentative problem structuring” and “visualizsation” separately. Concerning the visualization, I like just to point to the fact that Tim (with YourView), Simon (with the new ExpertHub) and Tom (with the latest edition of a structured-consultation tool based on Carneades) have turned away from using maps as a primary means for communication. (I also tried to translate the map into a structured-consultation tool lately: http://www.debattenprofis.de/praenatest/

4. Concerning the argumenative reconstruction: I am becoming more and more skeptical in regard to the benefits of rational reconstruction. Partly this is motivated by that sort of arguments brought forward by, Jonathan Dancy (e.g.: Dancy, J. (o.J.). Reasoning is no Inference. Abgerufen von http://experimentalphilosophy.typepad.com/2nd_annual_online_philoso/files/jonathan_dancy.pdf). One example for this: I observerved that participants of a discussion are not willing to consider something as a “prima facie” reason. / I also have encountered the situation that is often impossible to state the premisses of an argument without offending one of the conflicting parties. / Often, the final act of weighting the arguments is much more important than the arguments themselves. The reasoning that goes along with weighting offers many, many option. Any approach that tries to force readers to accept something like necessery conclusions (which in their view might not be necessary at all) will probably not be accepted by them. In other words: rational reconstruction and enabling participation might be conflicting goals.

Best,

Ralf

Ralf — thanks a lot for providing these constructive comments and sharing your experience! I appreciate points 1-3. We should be open-minded pluralists and try out a variety of tools for presenting argumentative analyses. I consider the argument browser a leightweight, flexible (and to some extent experimental) tool that can be enhanced in a modular way. May be we can have a more concrete discussion about features once it’s available.

Your point 4), I have to say, however, does not cohere with my own experience. It’s crucial to keep in mind that reconstruction is distinct from evaluation, right? To reconstruct an argument, making its hidden assumption explicit, has nothing to do with saying that some premisses are necessarily true and thence have to be accepted. Also, I agree that weighing arguments is of pivotal importance when you want to come to a conclusion given a complex debate. But detailed argument reconstruction, it seems to me, is a precondition for weighing the arguments in a proper way: As long as hidden assumptions are not unearthed, you might simply not see that an argument hinges on an implausible premiss and give it, as a consequence, too much weight.

But let’s continue this discussion!